One Man’s Mission to Capture India’s Disappearing Single Screen Theaters

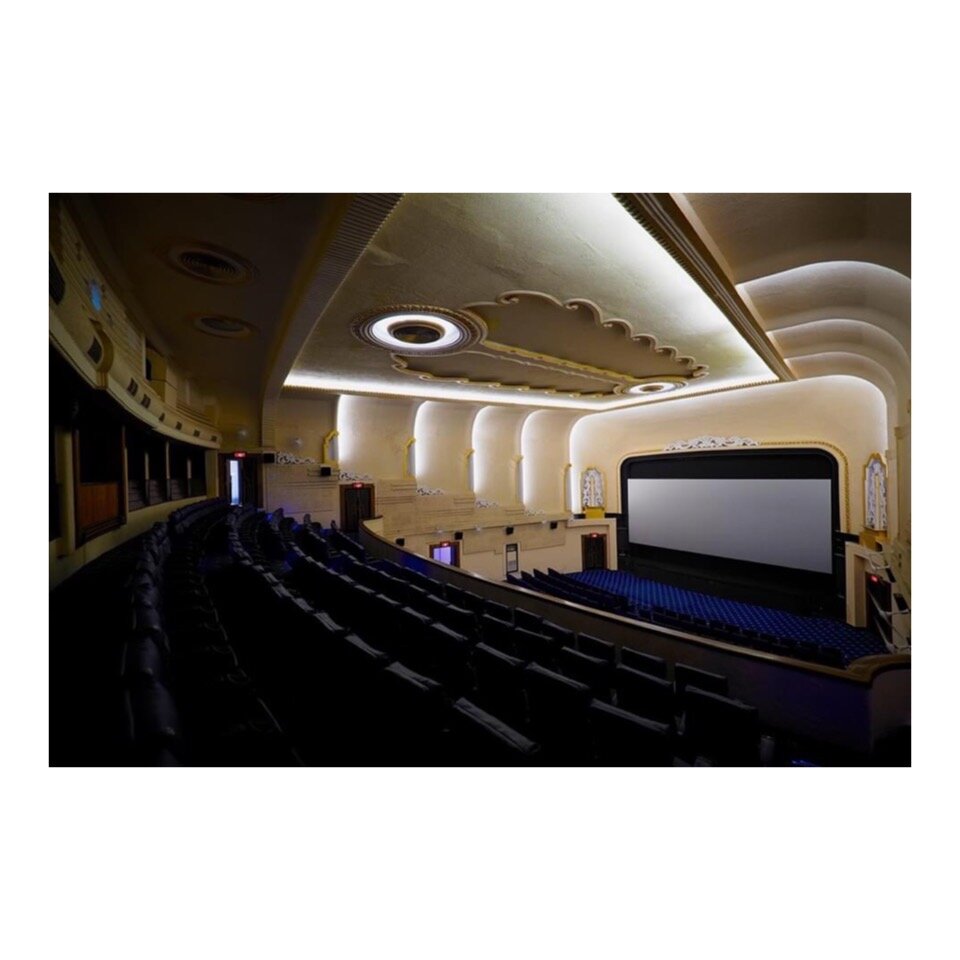

Hind Talkies, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh. Photo: Hemant Chaturvedi

Published on Fodor’s Travel - September 2021

Hemant Chaturvedi’s most ambitious photography project was the result of a deal gone wrong. In 2019, Chaturvedi was in the Indian city of Prayagraj (earlier known as Allahabad) to take pictures at the Kumbh Mela, a multi-day religious gathering that takes place every 12 years. The event is often billed as the largest gathering of humans on earth, and Chaturvedi had booked a tent within the Mela’s main area to stay during the festival, but it turned out to be a “complete hogwash” in his words. So, he moved to his ancestral home in another part of the city.

On an afternoon away from the festival, Chaturvedi decided to photograph parts of the old city. His wanderings led him to Lakshmi Talkies, an old single-screen theatre from the 1940s that he remembered from childhood visits. The Art Deco facade was still there, though not for long. Chaturvedi learned it was soon to be demolished.

He called in a few favors and got access to the theatre before the bulldozers arrived. Inside, he found a statue of the Goddess Lakshmi and Burma teak banisters carved in the Art Deco style. The seats were gone, but on either side of the cinema hall, he found 15 x 25-foot murals of scenes from the Ramayana, a major Indian epic.

The experience got him wondering about other single-screen theatres in the city. “I’ve seen Allahabad being eroded in the last 20 years in a manner that gives me the heebie-jeebies,” says Chaturvedi. “It’s happening across the country. We have no respect for our older structures and heritage.” He decided to photograph four theatres in the city before returning home to Mumbai.

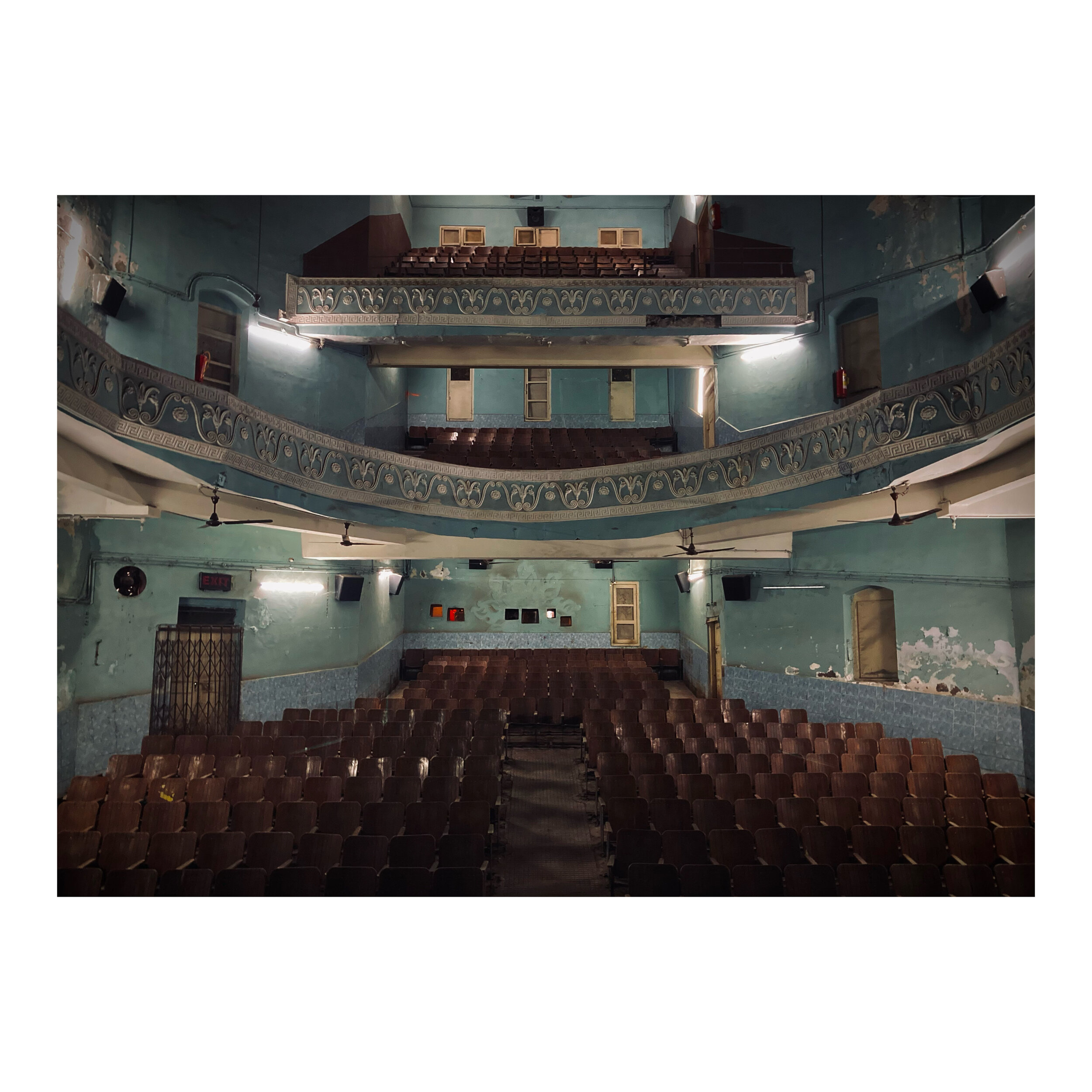

The pictures and conversations with cinema owners stayed with Chaturvedi long after his return. He did some digging and found out that between 2000 and 2019, about 12,000 single-screen cinemas had closed or were demolished. “It struck me that an entire history is being erased,” he said. He decided to embark on a project to visually document these theatres before it was too late.

India’s connection with motion picture films goes back to 1896 when the Lumiere brothers first screened movies at a Mumbai hotel. In 1913, Dadasaheb Phalke made Raja Harishchandra, India’s first full-length silent film. This was followed by Ardeshir Irani’s Alam Ara, the country’s first talking movie. Over time, regional cinema centers grew based on local languages. Though Bollywood (Hindi cinema) is the most popular export from India, it is by no means the only one.

Films made in languages—including Malayalam, Tamil, Bengali, Gujarati, and more—make India one of the world’s largest movie producers. Movie-watching in India evolved over the years, too. Films went from being projected on sheets tied between trees to single-screen cinema houses to multiplexes in the late 1990s.

“The all-abiding memory of a single-screen cinema is the kind of audience participation you get while watching a popular film in a houseful show,” said Chaturvedi, recalling the joy of going to old theatres. “In multiplexes, you can’t express yourself if you wish to because someone will shush you.” He’s right. It isn’t uncommon in some Indian theatres to have audiences hoot when the protagonist is first introduced on-screen or dance in the aisles when popular songs come on.

Following his 2019 Prayagraj photographs, Chaturvedi sought out and photographed some single-screen cinemas in Mumbai. A chance introduction with a cinema owner in the city of Nasik granted him access to theatres there, too. The thrill of the unknown is what drove Chaturvedi. “You have a Google Maps location and a name,” explains Chaturvedi. “Until you park your car in front of [the theater] and get out and look, you don’t know what you will find.”

Chaturvedi set out on extensive road trips across parts of western and northern India to shoot more theatres. Over two years, Chaturvedi drove more than 30,000 kilometers (nearly 19,000 miles) and photographed 655 cinemas in 500 towns across 11 states in India. He’s photographing a few more and is working on compiling the pictures into a book.

Getting access to these buildings was a game of chance. If the owners were around, it wasn’t too much trouble, but Chaturvedi had to get creative for old, abandoned theatres. Sometimes he’d scale boundary walls or push past loose bricks to get the perfect shot, but it was all worth it. His photo collection is a repository of cinematic jewels. There are unique weathered facades, beautifully restored cinema halls, forgotten movie posters, colonial-era box seats, abandoned equipment, and quaint ticket windows. In a small-town theatre in the state of Madhya Pradesh, Chaturvedi found empty alcohol bottles and piles of discarded 35mm film. At a Delhi theatre that had witnessed a deadly fire, he found burnt seats, and the iron door of the projection room melted shut.

Apart from the photos, Chaturvedi also collected stories from the people who owned and ran the cinemas. Wherever possible, he shot the projector operators together with their equipment. As a cinematographer, Chaturvedi was interested in the machines and would engage in conversations with the men who handled them. He recounted the story of Murali, a projectionist who started working on 35mm film projectors before being trained on digital ones. Chaturvedi asked him how he felt about the new machines.

Gurbaksh Singh and his meticulously restored 1939 Century Peerless 35mm projector in Patiala, Punjab.

“He told me that when he switched reels, at least the public knew there was a man in [the projection] room. If there was a problem, we would get curses. Now there are no curses. I crave them. No one knows I exist,” Chaturvedi recalls the man saying. “It was the sweetest thing I’ve heard, that he’s willing to hear abuses if someone just pays attention that a man is running the machine.”

That sentiment of recognition and acknowledgment is also why many cinema owners support Chaturvedi’s project. The photographs are a way for their legacies to be preserved forever. For many of them, running the theatre is a family business, and they view their cinemas as more than just buildings. An owner, whose father built the cinema and named it after his mother, said he would do whatever it takes to keep the theatre open because he couldn’t stand to see a building with his grandmother’s name on it be demolished.

Another owner, an elderly man, told Chaturvedi that it was one of his life’s greatest tragedies that his family theatre had closed on his watch, and he couldn’t reopen it. “I don’t know whether I’ll be alive when your book is ready, but at least I know my theatre is going to be immortalized somewhere,” Chaturvedi recalled the owner saying. “It won’t be forgotten.”

All photos courtesy Hemant Chaturvedi.